I watched it happen in real-time. A teacher posted something on Twitter (and it was that and not its unmentionable new name!) - a clumsy attempt at humour that landed badly. Within hours, the pile-on had begun. Dozens of people, many of them educators themselves, queued up to condemn. Not just to disagree or critique, but to dismiss entirely. “This person shouldn’t be in a classroom.” “Absolutely disgraceful.” “Career over, surely?”

And, many of these condemners would position themselves as lefty liberals too, open to freedom and discourse, rather than moral imperatives and religious fundamentalism. The irony would be unbelievable if it weren’t so damaging.

By the next morning, the teacher had deleted their account. Perhaps they’d learned their lesson. Perhaps they were shattered. Perhaps both. But what struck me most wasn’t the initial misstep - we’ve all made those - but the gleeful speed with which fellow professionals rushed to consign someone to the rubbish heap based on 280 characters.

We’ve become remarkably efficient at writing people off. A comment out of step with current thinking, a photo from a decade ago, a moment of poor judgement captured forever in digital amber - any of these can now serve as sufficient grounds for complete dismissal. Not just of the action or the idea, but of the entire person. Their past contributions don’t matter. Their capacity for growth is irrelevant. They’ve been judged, found wanting, and cast out.

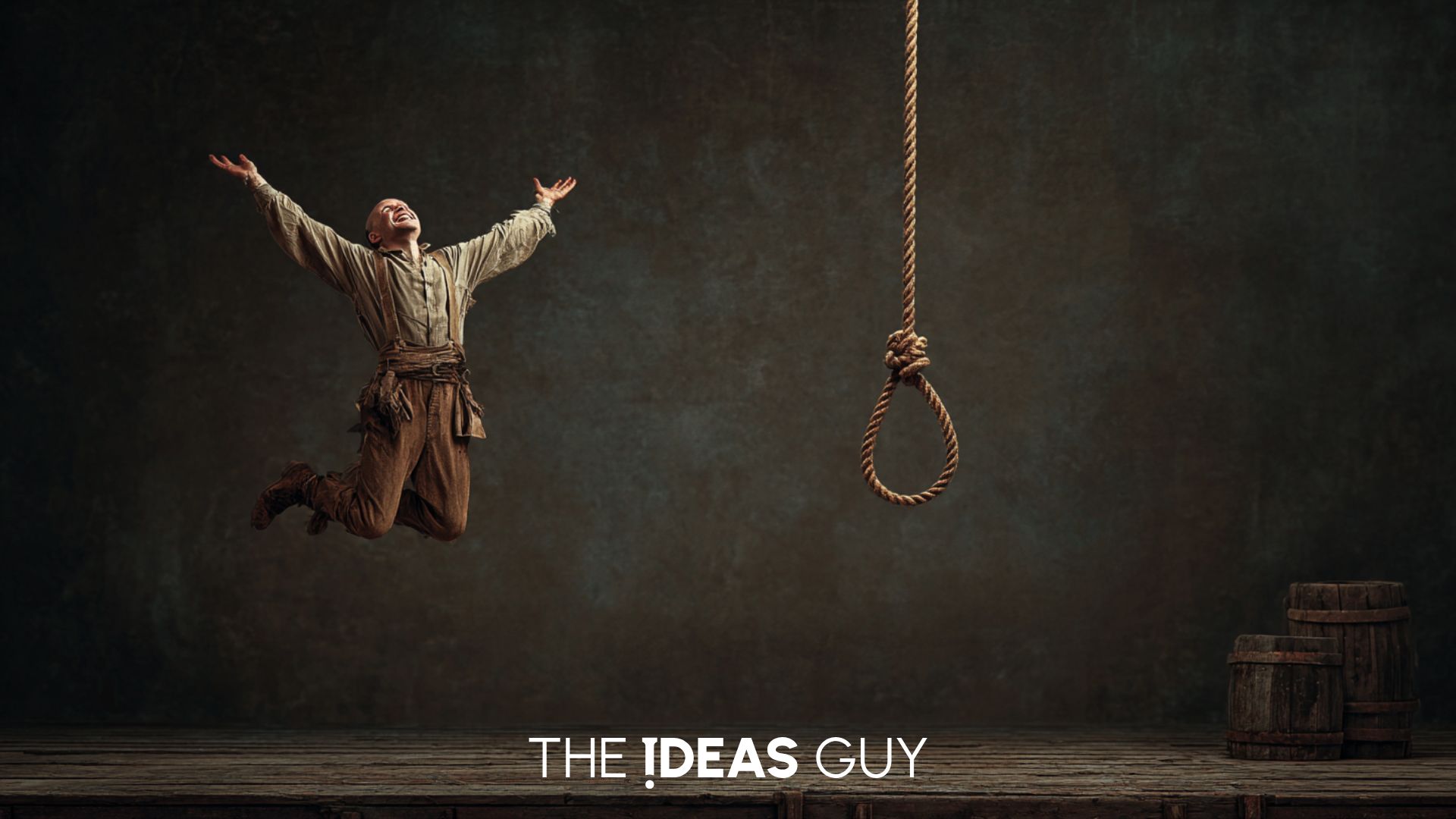

This isn’t justice. It’s not even particularly satisfying, despite what our dopamine receptors might tell us in the moment. It’s the wholesale abandonment of something humans have historically understood as essential to civilised coexistence: grace.

Grace is that unfashionable notion that we might extend understanding, second chances, or simple human decency to those who’ve stumbled. That we might see people as more than their worst moments. That condemnation might not be the only, or even the best, response to imperfection.

This piece isn’t a plea for moral relativism or a defense of genuinely harmful behaviour. It's not a religious piece spouting Christian values as if they should be posted on classroom walls (that is mental in the US by the way!) It’s an examination of what we’ve lost in our rush to judgment and what might be gained by cultivating what I’m calling a “disposition of grace” - not as weakness, but as a radical alternative to the exhausting economy of perpetual condemnation.

The Economics of Condemnation

Let’s be honest: judgment feels bloody brilliant. There’s an immediate psychological payoff to identifying someone else’s failing and declaring ourselves superior by comparison. The neuroscience is clear - our brains reward us for this behaviour. When we judge others, we activate reward centres associated with pleasure and satisfaction. We’re not just being mean; we’re getting high on our own moral certainty.

Friedrich Nietzsche understood this dynamic intimately. He called it ressentiment - the psychological state where we define our goodness primarily through condemning the badness of others. As he observed:

“The slave revolt in morality begins when ressentiment itself becomes creative and gives birth to values: the ressentiment of natures that are denied the true reaction, that of deeds, and compensate themselves with an imaginary revenge.” Friedrich Nietzsche

In other words, we build our sense of virtue not through what we do but through what we condemn. It’s morality on the cheap - no actual ethical effort required, just the identification of someone worse than ourselves.

Social media has industrialised this process. Every platform is essentially a ressentiment factory, churning out opportunities for us to perform our righteousness by identifying others’ failings. The algorithm doesn’t reward grace; it rewards engagement, and nothing engages quite like moral outrage. A measured, compassionate response to someone’s mistake might get a few likes. A withering takedown goes viral.

The anthropologist René Girard described how communities create cohesion through the identification and expulsion of scapegoats. We bind ourselves together not through shared values but through shared targets. The person we’re collectively condemning serves a crucial social function - they unite us in our certainty that we’re better than them.

This is particularly pronounced in British discourse, where we’ve developed sophisticated mechanisms for social policing through judgment. The cutting remark, the raised eyebrow, the “Well, that’s not on, is it?” These are the instruments through which we maintain social order and, more importantly, establish our place within the hierarchy of righteousness.

But what we rarely acknowledge is that this economy of condemnation is exhausting and ultimately unsustainable. Each judgment we render establishes a standard we ourselves must live up to. Every person we write off based on a single failing creates anxiety about our own inevitable stumbles. We’re building a world where none of us can afford to be human.

The cost isn’t just psychological. When we create environments where mistakes are met with complete dismissal rather than opportunities for growth, we stifle the very innovation and authenticity we claim to value. In schools, this manifests as students too terrified to take intellectual risks. In workplaces, it produces cultures of showy conformity where everyone’s too busy protecting their reputation to do anything genuinely creative.

We’ve confused discernment with condemnation, boundaries with banishment. And in doing so, we’ve lost something essential: the capacity to see each other as complex, evolving beings rather than fixed moral quantities to be sorted into acceptable and unacceptable categories.

What Grace Actually Means (And What It Doesn’t)

Before we go further, we need to clear up a fundamental misunderstanding: grace is not weakness. It’s not acceptance of harmful behaviour. It’s not “letting people off the hook” or pretending wrong doesn’t exist. These misconceptions are precisely why many people reject grace as a viable approach to navigating difference and conflict.

So what is grace?

The philosopher Emmanuel Levinas offers a starting point. His entire ethical framework rests on the encounter with the face of the Other - the moment when we recognise another person’s fundamental humanity and vulnerability. For Levinas, ethics doesn’t begin with abstract principles but with this visceral recognition that the person before us makes a claim on us simply by existing. As he wrote:

“The face is what forbids us to kill.” Emmanuel Levinas

This might sound dramatic in the context of everyday disagreements, but Levinas means it metaphorically as well as literally. When we truly encounter someone’s face, when we see them as a complete human being rather than as a representative of ideas we oppose, we’re confronted with an ethical demand. We cannot simply dismiss or destroy them without acknowledging what we’re doing.

Grace, in this framework, is the active choice to honour that encounter even when the other person has failed, stumbled, or acted harmfully. It’s the recognition that this person, like us, is imperfect, struggling, and capable of change. It doesn’t require us to approve of their actions or even to forgive immediately. It simply requires us to maintain their humanity in our eyes rather than reducing them to their worst moment.

Søren Kierkegaard approached grace from a different angle, seeing it as intrinsically bound up with authentic existence. For Kierkegaard, to live authentically means to acknowledge our own constant need for grace, our perpetual falling short of who we might be. From this recognition of our own insufficiency, we develop the capacity to extend grace to others. As he observed, true faith involves accepting that we exist in a state of constant becoming, never fully arrived, always in need of second chances.

This isn’t the same as having no standards or boundaries. Grace can coexist with firm limits on behaviour. I can extend grace to someone while still saying, “I won’t accept being treated this way,” or “This behaviour has consequences.” The difference is that I’m addressing the action without obliterating the person.

In Western culture, we often confuse tolerance with grace, but they’re distinct. Tolerance is passive - “I’ll put up with you even though I disapprove.” Grace is active - “I recognise your humanity even in your failing.” Tolerance often carries resentment; grace creates possibility.

This distinction matters enormously in educational contexts. A tolerant teacher might refrain from expelling a student who’s made a mistake while internally writing them off. A gracious teacher maintains belief in the student’s capacity for growth even while holding them accountable for their actions. The external responses might look similar, but the internal posture - and the message it communicates - is radically different.

Paul Ricoeur’s philosophy of recognition offers another layer. Ricoeur argued that genuine recognition involves seeing the other as a subject with their own agency and narrative, not as an object to be categorised. When we extend grace, we’re practising what he calls “mutual recognition” - acknowledging that the other person’s story is as complex and valid as our own, even when our stories conflict.

Grace, then, is neither weakness nor foolishness. It’s the strength to maintain complexity in a world that constantly pressures us toward simplification. It’s the wisdom to recognise that today’s condemned might be tomorrow’s redeemed because people change, contexts shift, and our own understanding evolves.

The Paradox of Self-Righteousness

Our harshest judgments of others often reveal more about us than about them. The qualities that most infuriate us in other people are frequently the very traits we’ve disowned or suppressed in ourselves.

Carl Jung called this “shadow work” - the recognition that what we most vehemently condemn in others is often what we cannot face in ourselves. As he observed:

“Everything that irritates us about others can lead us to an understanding of ourselves.” Carl Jung

This isn’t pop psychology nonsense. It’s a deep psychological mechanism. When we encounter someone expressing a quality we’ve worked hard to eliminate from our own behaviour - perhaps entitlement, or selfishness, or intellectual laziness - our reaction is often visceral and disproportionate. We’re not just judging their action; we’re reinforcing our own internal prohibition against similar behaviour.

Jean-Paul Sartre’s concept of “bad faith” illuminates another dimension of this dynamic. We engage in bad faith when we deny our own freedom and responsibility by identifying entirely with social roles or fixed identities. The teacher who condemns another teacher’s mistake with particular venom might be in bad faith about their own vulnerability to similar errors. By casting themselves as fundamentally different, as someone who would never do such a thing, they deny their own capacity for failure and, paradoxically, make themselves less able to avoid it.

This connects to what psychologists call the “fundamental attribution error” which is our tendency to attribute others’ mistakes to their character while excusing our own as circumstantial. When I arrive late to a meeting, it’s because traffic was terrible and my previous meeting ran over. When you arrive late, it’s because you’re disorganised and don’t respect others’ time. This cognitive bias isn’t just sloppy thinking; it’s self-serving and ultimately corrosive to any possibility of grace.

The biblical story about logs and specks captures this dynamic perfectly, though we needn’t frame it religiously to recognise its psychological insight. We’re acutely sensitive to minor failings in others while remaining oblivious to our own more significant flaws. Or as Marcus Aurelius, writing from Stoic philosophy rather than Christian tradition, put it:

“How much more grievous are the consequences of anger than the causes of it.” Marcus Aurelius

We damage ourselves and our communities more through our judgment than through the original transgression we’re judging. The energy we expend on condemnation, the relationships we fracture through dismissal, the environments of fear we create - these consequences often dwarf whatever harm prompted our initial outrage.

I’ve seen this play out repeatedly in educational settings. A senior leader becomes incandescent about a teacher’s failure to follow a particular procedure, perhaps something genuinely important about safeguarding. But the fury with which they respond, the public humiliation they inflict, the complete dismissal of the teacher’s years of otherwise exemplary service - all of this creates far more damage than the original oversight. And often, upon examination, the leader’s extreme response stems from their own anxiety about being seen as insufficiently rigorous rather than genuine concern for students.

I saw it with an old colleague of mine who had led his department with military precision. He was an exemplary teacher, who students and parents loved, other teachers respected and who the leaders paraded out in front of other schools consistently. When one set of results went awry (not his but his department’s) and some staff absences went above threshold, he was hauled over the coals and put on a performance management plan. No grace or understanding, pure filthy judgment.

This is what Hannah Arendt understood when she distinguished between thoughtlessness and evil. Many harmful actions stem not from malicious intent but from failure to think through consequences, from acting on autopilot, from succumbing to social pressure. Arendt’s analysis of Adolf Eichmann remains controversial, but her core insight stands:

“The sad truth is that most evil is done by people who never make up their minds to be good or evil.” Hannah Arendt

If we accept this - that most harm stems from human limitation rather than malice - then our project becomes fostering conditions for thoughtfulness rather than perfecting our ability to identify and expel the wicked. Grace creates space for reflection and growth; condemnation forecloses it.

The paradox, then, is this: the more confidently we condemn others, the more we reveal our own brittleness. The more harshly we judge, the more we demonstrate our own fragility. True strength - the kind that can afford to extend grace - comes from accepting our own imperfection and capacity for error.

Grace as Radical Practice

If grace isn’t weakness, what does it actually look like in practice? How do we extend it without becoming doormats or enabling genuinely harmful behaviour? This is where theory must become action, where philosophy must descend from abstraction into the messy reality of human interaction.

Hannah Arendt offers a provocative starting point. In The Human Condition, she argues that forgiveness, a close cousin of grace, is not merely personal virtue but political necessity. Without the capacity to forgive and begin again, human communities would be paralysed by the weight of accumulated resentments and past wrongs. As she writes:

“Forgiveness is the key to action and freedom.” Hannah Arendt

This is radical because it reframes grace as empowering rather than soft. When we extend grace, we’re not simply being nice; we’re creating the conditions for forward movement. We’re refusing to let past actions completely determine future possibilities. In workplaces, schools, or communities, this capacity to reset relationships after conflict is essential infrastructure, not moral luxury.

But Arendt is clear: forgiveness (and by extension, grace) cannot be demanded or coerced. It’s freely given or it’s not genuine. This means that extending grace must be a choice we make, not an obligation imposed on us. When institutions mandate that we “move on” or “let it go” without addressing legitimate grievances, they’re not fostering grace, they’re enforcing suppression of legitimate anger.

Ricoeur again distinguishes between “cheap grace” and what we might call authentic grace. Cheap grace pretends nothing wrong occurred. It papers over harm in the name of superficial harmony. Authentic grace, by contrast, acknowledges wrong fully while choosing not to let it be the final word. It’s the difference between “It wasn’t really that bad” and “It was that bad, and I’m choosing to create space for something different to emerge.”

In practical terms, this might look like a headteacher addressing a serious safeguarding error. A cheap grace approach would minimise: “We all make mistakes, let’s just move on.” An authentic grace approach would say: “This was a serious failing with real consequences. We’ll address those consequences, implement better systems, and support your development. This doesn’t define you completely, but it demands response and growth.”

The key distinction is that grace doesn’t erase accountability; it contextualises it within a broader understanding of human complexity and capacity for change.

This might mean:

- Assuming good intent until proven otherwise

- Asking clarifying questions before condemning

- Acknowledging context without excusing harm

- Maintaining curiosity about another’s perspective even when we disagree strongly

- Separating the person from the action in our internal dialogue

- Recognising our own capacity for similar failings

These practices aren’t particularly dramatic, which is precisely why they’re sustainable. Grand gestures of forgiveness make for good cinema but rarely for good daily practice. It’s the accumulated small choices to extend grace that transform our character and our communities.

I’ve learned this the hard way. For years, I prided myself on being generous with others while maintaining impossibly high standards for myself. I thought this was virtuous. In reality, it was exhausting and ultimately unsustainable. The same merciless inner voice I used on myself would occasionally leak out onto others when my resources were depleted. It was only by extending myself some of the grace I was so ready to offer others that I developed a truly gracious disposition rather than a fragile performance of magnanimity..

The Stoics offer a final insight here. Epictetus taught that we should distinguish rigorously between what is in our control and what isn’t. We cannot control others’ actions, but we can control our response. Grace, in this framework, is the choice to respond to others’ failings with equanimity rather than outrage, not because we approve, but because outrage serves neither us nor them.

“When you wake up in the morning, tell yourself: The people I deal with today will be meddling, ungrateful, arrogant, dishonest, jealous and surly. They are like this because they can’t tell good from evil.” Marcus Aurelius

The Personal Cost of Ungrace

While we’ve examined the social and ethical dimensions of grace, we’ve barely touched on something equally important: the profound personal toll that perpetual judgment exacts on the one doing the judging.

Living in a state of constant condemnation is exhausting. It requires enormous psychic energy to maintain vigilance against others’ failings, to police boundaries of acceptability, to perform righteous outrage on cue. And unlike physical exhaustion, which we generally recognise and address, moral exhaustion often masquerades as virtue. We tell ourselves we’re staying alert, maintaining standards, refusing to be complicit. But we’re actually corroding our own capacity for joy, connection, and peace.

Research in positive psychology bears this out. Studies consistently show that people who habitually hold grudges, ruminate on others’ wrongdoing, and maintain rigid moral judgments experience higher rates of depression, anxiety, and stress-related illness. The body keeps score of our unforgiveness just as surely as it does our forgiveness. When we write people off, we’re not just affecting them, we’re poisoning ourselves.

Epictetus argued that we harm ourselves far more through our reactions to others’ behaviour than through the behaviour itself:

“It is not things themselves that disturb people, but their judgements about those things.” Epictetus

When someone behaves badly toward us and we respond with sustained resentment and judgment, we’ve allowed them to continue harming us long after the initial transgression. We’ve given them residence in our mind, space in our inner dialogue, power over our emotional state. Marcus Aurelius framed it even more starkly:

“The best revenge is not to be like your enemy.” Marcus Aurelius

By responding to others’ failures with gracelessness, we become the very thing we condemn - people who cause harm through their actions.

But beyond the physiological and psychological costs, living without grace imposes a spiritual toll. I use “spiritual” here not in any religious sense but to describe what it feels like to be fundamentally us. It’s our capacity for wonder, connection, and meaning-making. Perpetual judgment shrinks our inner world. It makes us smaller, meaner, more brittle versions of ourselves.

I saw this most clearly during a particularly brutal period in my own leadership. I’d convinced myself that maintaining “high standards” required being merciless in my assessments of colleagues’ performance. Every failing was noted, every shortcoming catalogued. I told myself I was being professional, holding people accountable. In reality, I was creating a culture of fear and making myself miserable in the process.

The turning point came when a trusted colleague - someone brave enough to risk my disapproval - asked me a simple question: “Do you actually like anyone you work with?” I was stunned. Of course I did. But as I reflected, I realised that my constant judgment had so dominated my thinking that I’d lost touch with my genuine affection and respect for these people. I’d reduced them to their failures in my own mind, and in doing so, I’d lost something essential in myself.

I’m not suggesting dealing with any of this is easy. I’ve spent years in therapy working through genuine harms done to me by others, learning to distinguish between healthy boundaries and toxic resentment. The goal isn’t to bypass legitimate anger or to pretend harm didn’t occur. It’s to prevent those legitimate grievances from calcifying into a permanent state of ungrace that ultimately harms us more than the original wrong.

The novelist Anne Lamott captures this with characteristic bluntness:

“Not forgiving is like drinking rat poison and then waiting for the rat to die.” Anne Lamott

We think our judgment and unforgiveness are weapons we’re deploying against those who’ve wronged us. In reality, we’re the ones ingesting the poison.

This matters enormously in educational contexts because students are exquisitely attuned to whether adults genuinely believe in their capacity to change. A teacher who maintains a graceless stance toward a student who’s struggled, who internally writes them off while going through the motions of support, communicates that assessment more powerfully than any explicit words. And students, internalising that judgment, often fulfil the prophecy.

I’ve watched this dynamic play out countless times. A student makes a serious mistake. Adults respond with consequences, which are appropriate. But some adults extend those consequences indefinitely in their minds, continuing to view the student through the lens of that mistake years later. “Oh, that’s the one who…” becomes the defining description. The student senses this ongoing judgment and either internalises it (“I’m the person who makes those mistakes”) or rebels against it (“You’ve already decided I’m bad, so I might as well act accordingly”).

The cost of this ungrace isn’t just to the student’s development, it’s to the adult’s own humanity. To maintain a perpetual stance of judgment requires constant vigilance and emotional labour. It’s exhausting, and it prevents us from experiencing the genuine satisfaction that comes from witnessing real growth and transformation.

We cause ourselves unnecessary suffering by demanding that the world and people be other than they are. Again, the ever-wise Epictetus taught his students to distinguish between what is “up to us” (our own choices, responses, and character) and what is “not up to us” (others’ behaviour, external events, circumstances). We suffer most when we try to control what isn’t up to us, when we demand that others meet our standards rather than accepting them as they are and working with that reality.

This isn’t resignation or passivity; it’s radical acceptance that frees us to respond effectively rather than react emotionally. When I accept that people are flawed, that mistakes will happen, that growth is slow and non-linear, I free myself from the constant disappointment and anger that comes from expecting otherwise. I can then extend grace not as a favour to them but as a gift to myself - the gift of freedom from the exhausting work of judgment.

Building a Disposition of Grace

So how do we cultivate this disposition of grace when everything in our culture pushes us toward judgment? How do we develop the strength to extend understanding when condemnation feels so satisfying? This isn’t about personality transplants or becoming someone we’re not but it’s about deliberate practice that gradually reshapes our reflexive responses.

Aristotle’s insight that we become virtuous through repeatedly acting virtuously applies perfectly here. We don’t wait until we feel gracious to act graciously; we act graciously until it becomes our nature. This is the work of character development, and like all such work, it requires intentionality, repetition, and patience.

Start with self-grace. This is non-negotiable. If you cannot extend grace to yourself, any grace you offer others will be performative and unsustainable. Pay attention to your inner dialogue. How do you speak to yourself when you make mistakes? Would you talk to a friend that way? The harshness we direct inward almost inevitably leaks outward eventually.

Buddhist teacher Pema Chödrön offers practical wisdom here. She suggests that when we notice ourselves in self-judgment, we pause and place a hand on our heart - a simple physical gesture that activates our self-compassion systems. This isn’t touchy-feely nonsense; it’s neuroscience. Physical gestures of self-kindness actually shift our nervous system toward states more conducive to compassionate responses.

Cultivate curiosity before judgment. This is perhaps the single most powerful practice for developing grace. When you encounter something that triggers judgment - a colleague’s behaviour, a policy you disagree with, a student’s choice that baffles you - pause and ask, “What might make this make sense?” Not “What excuse can I imagine?” but genuinely, “From what perspective does this seem reasonable?”

This is what phenomenologists call “bracketing” which is temporarily setting aside our own framework to understand another’s. It doesn’t require agreeing with them, but it does require genuinely attempting to understand their logic, their constraints, their circumstances. Often, this simple practice transforms our response from judgment to understanding, from condemnation to constructive engagement.

Practise the “yes, and” rather than “yes, but.” This principle from improvisational theatre (which I learned from Neil Mullarkey) translates powerfully to grace. When someone fails or falls short, our habitual response is often “Yes, I see what you tried to do, but…” which effectively negates whatever acknowledgment came before it. Grace sounds more like: “Yes, I see what you tried to do, and here’s what got in the way, and here’s what we might try differently.”

The structure matters because it maintains both accountability and possibility. It doesn’t excuse poor performance, but it doesn’t foreclose on future capacity either. This linguistic shift gradually rewires our thinking, making us more likely to hold complexity rather than rushing to simplistic judgments.

Create deliberate space between stimulus and response. Viktor Frankl, whose philosophy I reference repeatedly because it’s so foundational to my thinking, identified this as the essence of human freedom:

“Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.” Viktor Frankl

When someone does something that triggers our judgment, we can practise inserting even a momentary pause - a breath, a count to three, a brief walk - before responding. This tiny gap is where grace becomes possible. It’s where we move from reactive condemnation to considered response. (Some of you will remember my primary headteacher, Mr Haslam’s parting message in my leavers’ book was to count to 5 before saying what I think!)

Develop grace accountability partnerships. Find someone you trust to gently point out when you’re slipping into ungrace. Give them explicit permission to question your judgments, to ask whether you’re being as gracious as you could be, to remind you of your own commitment to this disposition. We cannot see our own blind spots; we need others to illuminate them.

This isn’t about being called out harshly for every judgment as that would just create another arena for ungrace. It’s about having someone who loves you enough to help you be the person you’re trying to become. My wife does this for me regularly, usually with a gentle “Is that really what they meant?” when I’m spinning up a storm of righteous indignation about someone’s behaviour.

Practise “metta” meditation or similar loving-kindness practices. Even if you’re not remotely Buddhist (as I am not), the formal practice of extending goodwill to all beings, starting with yourself, moving to loved ones, then to neutral parties, then to difficult people, literally rewires your brain. Neuroimaging studies show that regular loving-kindness meditation increases activation in brain areas associated with empathy and emotional regulation.

The format is simple: sit quietly and repeat phrases like “May I be happy. May I be healthy. May I be safe. May I live with ease.” Then extend the same wishes to others. It feels awkward at first, particularly when you reach the “difficult people” category. That awkwardness is the feeling of your habitual judgment being challenged. Stay with it.

Seek out counter-narratives. We live in echo chambers that reinforce our judgments. Deliberately expose yourself to perspectives that challenge your certainties. Read thinkers you disagree with not to mock them, but to genuinely understand their reasoning. Follow people on social media who see the world differently. Attend events that attract audiences unlike you.

This isn’t relativism because you don’t have to abandon your convictions. But understanding how someone reaches different conclusions, even wrong ones, cultivates the intellectual humility necessary for grace. It reminds us that certainty is often a function of perspective and information access, not moral superiority.

Accept that grace is often unrequited. One of the hardest aspects of cultivating a gracious disposition is that many people won’t reciprocate. You’ll extend understanding, and they’ll remain defensive. You’ll offer a gracious interpretation, and they’ll attack you anyway. This is where we discover whether we’re truly committed to grace or whether we’re just deploying it strategically to get better treatment.

Marcus Aurelius reminds himself that virtue is its own reward as we act rightly because it’s right, not because it guarantees a particular outcome. Grace extended is its own good, regardless of whether it’s received. This is extraordinarily difficult to internalise, but it’s essential. Otherwise, we’re not really practising grace; we’re just making calculations about what behaviour will yield the best results.

Cultivating a disposition of grace isn’t sentimental self-help; it’s pragmatic wisdom for navigating human complexity.

Further Reading

Discover more interesting articles here.

.png)

.jpg)