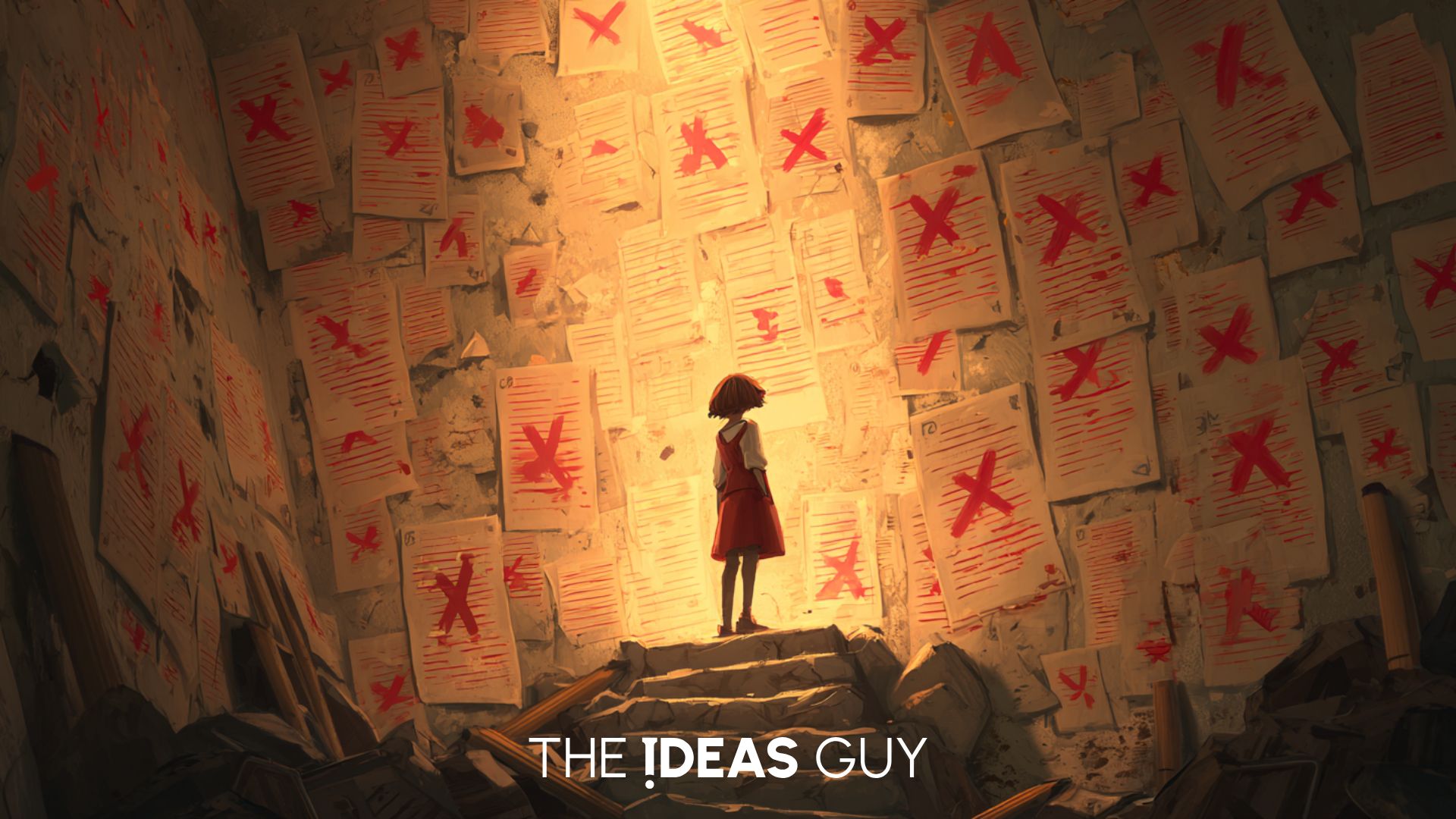

Every failure becomes curriculum for better judgment. This simple truth should be carved into the entrance of every school in Britain, yet our education system seems designed to prevent this natural learning process from occurring.

We've created institutions that are brilliant at teaching students to avoid failure but catastrophically poor at teaching them to learn from it. In doing so, we're not just failing our young people academically; we're failing to prepare them for a world where the ability to extract wisdom from setbacks isn't just useful but essential for survival.

The irony is brutal. We spend years protecting students from the very experiences that would develop their judgment, then release them into the world that demands exactly the kind of resilient thinking that only comes from learning through failure.

The Psychology of Learning Through Failure

The evidence for learning through failure is extensive. The neuroscientist Arne Dietrich's research on cognitive flexibility reveals something fascinating about how our brains actually change when we encounter unexpected results. What he calls "transient hypofrontality" occurs when our usual thinking patterns are disrupted by failure, temporarily reducing the dominance of our prefrontal cortex and allowing more creative connections to emerge. Failure literally rewires us for better thinking.

“The explicit system is very complex and depends largely, but not exclusively, on frontal cortical activation.It is primarily the source of our cognitive flexibility, abstract thinking and higher cognitive functions. But it has one large drawback, and that is the drawback that all complex machines have - complexity makes a machine slow. So we also have another system that has a completely different architecture. It is built for speed and efficiency, and the only way you can have speed and efficiency, when you’re very quick with sensory input and motor output, is when you automatise very quick movements. These systems need to be built in a simple, computational form, and that is what the implicit system does.” Arne Dietrich

Most education focuses on transmitting what Gilbert Ryle called "knowing that"; factual information students can recite. But judgment develops through "knowing how"; practical wisdom that only emerges through navigating actual difficulties. You can't develop "knowing how" without encountering situations where your current knowledge proves insufficient.

The anthropologist James C. Scott's concept of ‘metis’ - practical wisdom gained from local experience - offers another lens (one not too dissimilar to Aristotle’s phronesis). Scott argues that the most important knowledge comes from wrestling with the specific, messy realities of particular situations. This kind of wisdom can't be taught through textbooks; it must be earned through what he calls "the friction of practice" - including the friction of getting things wrong.

“But all these systems of ‘education’ lack provisions for freedom of experiment, for training and for expression of creative abilities by those who are to be taught. In this respect also all our pedagogues are behind the times.” James C. Scott

The psychologist Jerome Bruner also distinguished between two modes of thinking: the "paradigmatic" mode that seeks logical consistency and the "narrative" mode that makes sense of experience through story. Failure disrupts paradigmatic thinking and forces us into narrative mode - we must construct meaning from what went wrong. This narrative construction is where wisdom develops.

Nassim Taleb's concept of "antifragility" applies directly to learning. Some systems merely resist damage (robust), others recover from it (resilient), but antifragile systems actually get stronger from good stress. Students who never encounter meaningful failure develop fragile knowledge structures that collapse under pressure. Those who learn to extract value from setbacks develop antifragile minds that improve through challenge.

The Institutional Resistance to Failure

British education has developed an almost pathological aversion to student failure. This isn't because educators don't understand its importance; it's because every system pressure works against allowing meaningful failure to occur.

Ofsted inspections rarely reward schools that allow students to struggle and fail in service of deeper learning (even with their new Nando’s report cards!). League tables don't measure how well schools teach students to recover from setbacks. Progress 8 scores don't capture whether students are developing the judgment that comes from working through genuine challenges.

Parents, understandably anxious about their children's futures, often pressure schools to ensure success rather than meaningful learning. The complaint "Why didn't the teacher prevent my child from making that mistake?" is far more common than "How is my child learning from their errors?"

Teachers, facing accountability pressures, develop elaborate scaffolding systems designed to guide students toward correct answers without the messiness of genuine exploration (this is the polite way to say “spoon-feeding”). The unintended consequence is students who can follow instructions but can't navigate ambiguity.

Assessment systems compound the problem by treating wrong answers as simply deductions from a perfect score rather than as valuable diagnostic information. A student who gets 7 out of 10 on a test has learned something important from those three mistakes, but our systems are designed to focus on the deficit rather than the learning opportunity.

Where Failure-Positive Education Actually Works

Finland's education system, often cited for its excellence, takes a fundamentally different approach to failure. Finnish teachers are trained to view student mistakes as windows into thinking processes rather than problems to be eliminated. The assessment system is designed around learning progression rather than error avoidance.

The Norwegian concept of "friluftsliv" extends into their educational philosophy. Students are expected to encounter challenges they might not overcome on their first attempt. The cultural understanding is that character develops through working with difficulty, not around it.

Japanese education, despite its reputation for rigour, incorporates "kaizen" thinking into classroom practice. Continuous improvement is understood to require continuous engagement with what isn't working yet. Students are taught to see failure as information rather than judgment.

In contrast, the American approach of "failure parties" in some progressive schools represents the opposite extreme. Celebrating failure without extracting learning creates a different kind of dysfunction. So, it’s not either-or. Failure needs to be accepted but not at the expense of progress.

The Judgment Gap

When we prevent students from engaging meaningfully with failure, we create what might be called "the judgment gap". These are young people who can perform well in structured environments but collapse when faced with genuine uncertainty or setback.

University admissions tutors increasingly report encountering students who have excellent grades but seem unable to cope when things don't go according to plan. They've been so protected from failure that they haven't developed the psychological tools to process and learn from it.

Employers describe graduates who can execute tasks perfectly when given clear instructions but struggle when asked to navigate ambiguous problems where the solution isn't predetermined. They've learned to be right but not to be resilient.

Mental health services report growing numbers of young people who experience normal setbacks as catastrophic failures. Without the inoculation that comes from smaller failures, they haven't developed the emotional vocabulary and coping strategies that resilience requires. In my own teenager’s life, there is a real challenge to see a setback as a stepping stone rather than the end. If she has a bad day, everything is bad!

Building Failure Into Curriculum Design

Creating space for meaningful failure within educational frameworks requires deliberate design. This isn't about making things arbitrarily difficult or removing all support. It's about creating what educational psychologists call "desirable difficulties" that promote deeper learning.

Mathematics education offers a clear example. Instead of teaching procedures first and then applying them to problems, effective approaches present problems first and allow students to wrestle with them before introducing efficient methods. The initial struggle and likely failure becomes curriculum for understanding why the procedures work.

Science education benefits enormously from hypothesis-testing approaches where students make predictions that turn out to be wrong. The cognitive dissonance between expectation and reality creates the motivation for deeper investigation.

History education gains depth when students encounter conflicting sources and must grapple with the reality that simple narratives often don't hold up under scrutiny. The failure to find easy answers becomes the beginning of historical thinking.

English literature becomes more meaningful when students encounter texts that resist their initial interpretations, forcing them to develop more sophisticated reading strategies. The list could go on.

The Leadership Challenge

Implementing failure-positive education requires courage from school leaders. It means accepting that test scores might initially dip as students learn to engage with genuine challenges. It means having difficult conversations with parents about why their children need to struggle sometimes.

It requires training teachers to recognise the difference between productive failure and destructive frustration. Not all failures are equally valuable; some are simply demotivating without offering learning opportunities.

School leaders must develop assessment systems that capture learning from failure, not just achievement despite it. This might mean portfolio approaches that document learning journeys, including setbacks and recoveries.

Communication with stakeholders then becomes crucial. Parents need to understand why their children are being allowed to fail at some things. Governors need to see evidence that failure-positive approaches actually improve long-term outcomes. And those pesky inspectors should have a whole heap of failure-positive examples thrust upon them if they dare to just talk about the robust data!

The Philosophical Foundation

The reluctance to allow meaningful failure in education reflects deeper philosophical assumptions about childhood, learning, and human development. We've inherited Victorian notions that children are fragile vessels that need protecting rather than resilient learners who need challenging. (This runs deeper than just education too with the cotton-wool society we have created but that’s beyond today’s scope of writing!)

The philosopher John Dewey understood that genuine education comes through experience, including the experience of having our expectations confounded. His philosophy of learning through doing necessarily includes learning through failing. I used his quote last week but it bears repeating,

“We always live at the time we live and not at some other time, and only by extracting at each present time the full meaning of each present experience are we prepared for doing the same thing in the future.” John Dewey

The sociologist Donald Schön's work on reflective practice reveals how professionals actually develop expertise. They don't simply apply learned rules; they engage in what he calls "reflection-in-action" when their usual approaches prove inadequate. This reflection emerges precisely from the moment when things don't work as expected.

And then cognitive scientist Douglas Hofstadter's research on analogical thinking shows that we develop understanding by recognising patterns across different domains. But pattern recognition requires encountering situations where our initial pattern matching fails, forcing us to search for deeper, more abstract similarities. And this becomes more important as we navigate the nuances of AI-enhanced education - AI is generally much better at pattern recognition than we are so we need to work with it not against it.

Creating failure-positive learning environments starts with changing the language we use around mistakes. Instead of "That's wrong," effective teachers say "That's interesting, tell me more about your thinking." Assessment practices need fundamental revision. Instead of simply marking answers right or wrong, effective approaches ask students to explain their reasoning and reflect on where their thinking needs adjustment.

Project-based learning naturally incorporates failure when projects are genuinely challenging rather than carefully orchestrated to ensure success. Students working on real problems encounter real obstacles that require genuine problem-solving. Peer learning becomes more powerful when students are allowed to learn from each other's mistakes rather than only from their successes. Collaborative problem-solving creates opportunities for collective learning from failure.

The Courage Required

Perhaps most fundamentally, failure-positive education requires courage from everyone involved. Students need courage to take intellectual risks. Teachers need courage to allow students to struggle without immediately intervening. Leaders need courage to defend approaches that might temporarily depress test scores.

This courage is grounded in a deeper understanding of what education is actually for. If the purpose is to produce young people who can navigate an uncertain world with resilience and wisdom, then engaging with failure isn't just helpful but essential.

The alternative is continuing to produce graduates who can perform well in predictable environments but crumble when faced with genuine challenges. As the world changes faster than you can spell AI, not doing something about this is educational malpractice at best, gross negligence at worst.

Key Takeaways

Reframe failure as information. Train students and teachers to view mistakes as diagnostic data about thinking processes rather than indicators of inadequacy. Every wrong answer contains valuable information about how learning is progressing.

Design productive struggles. Create learning experiences where initial failure is likely but learning is possible. The struggle between current understanding and new challenges is where real learning happens.

Assess learning from failure. Develop assessment approaches that capture how students process and learn from mistakes, not just their ability to avoid them. Portfolios, reflective journals, and process documentation can capture this learning. This needs to be systemic too so we need the assessment and awarding bodies to listen up.

Train emotional resilience. Explicitly teach students how to process the emotions that accompany failure without becoming overwhelmed. This includes developing vocabulary for describing setbacks and strategies for working through them.

Change leadership conversations. Help school leaders, governors, and parents understand that some apparent short-term setbacks might be necessary for long-term learning gains. Failure-positive education requires different success metrics.

Model learning from failure. Teachers and leaders who openly discuss their own mistakes and what they learned from them create cultures where failure becomes acceptable curriculum rather than something to hide.

Create psychological safety. Ensure that classrooms feel safe enough for students to take intellectual risks without fear of humiliation or lasting negative consequences.

The fundamental truth remains: every failure becomes curriculum for better judgment if we reflect on it. Education systems that resist this natural learning process aren't protecting their students; they're disabling them. In a world where adaptability and resilience matter more than the ability to avoid mistakes, failure-positive education isn't just pedagogically sound but morally essential.

The choice is stark: we can continue producing young people who are brittle under pressure, or we can create educational environments that develop genuine wisdom through engagement with difficulty. The future belongs to those who can learn from their failures, not those who have been protected from them.

Further Reading

Discover more interesting articles here.

.png)